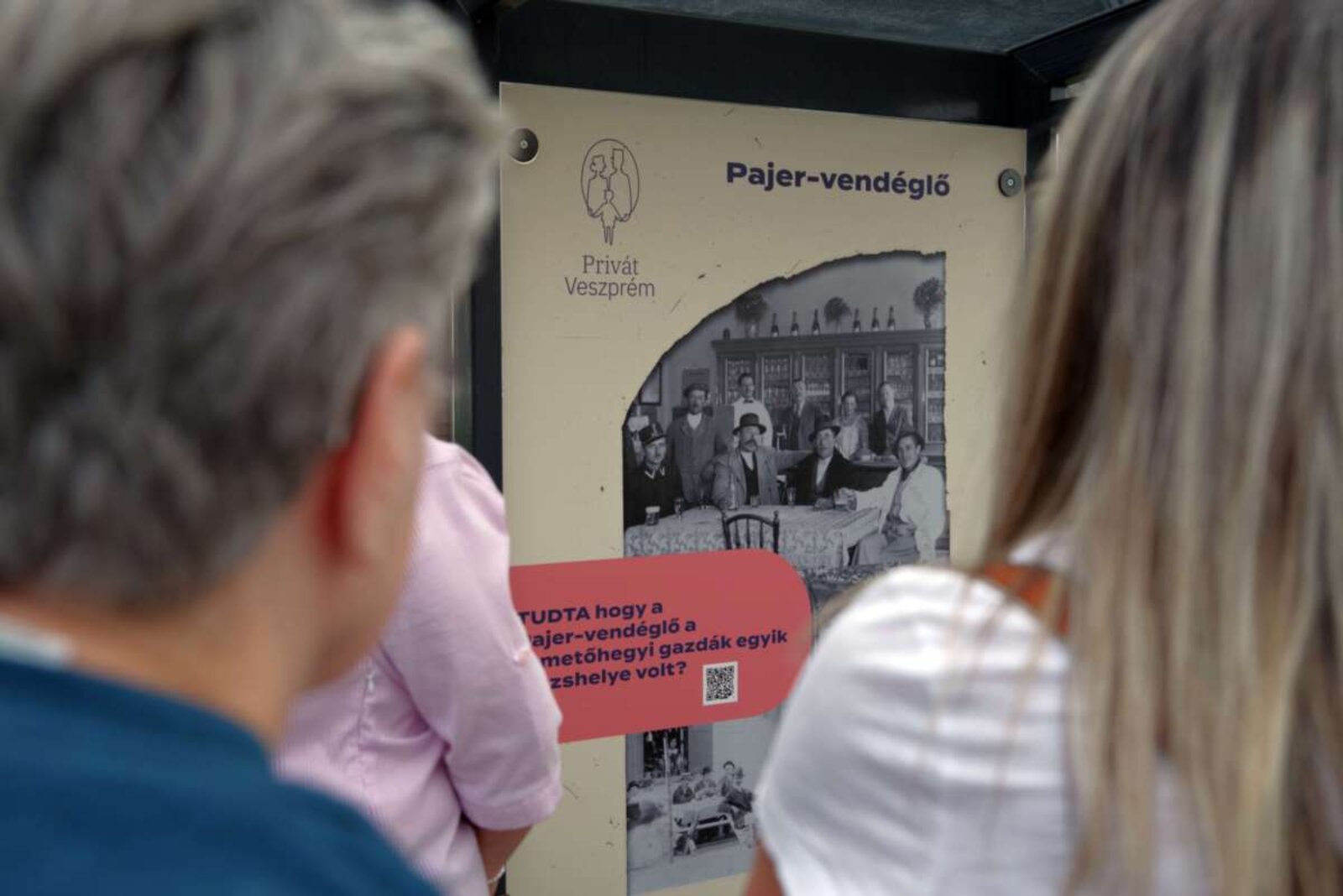

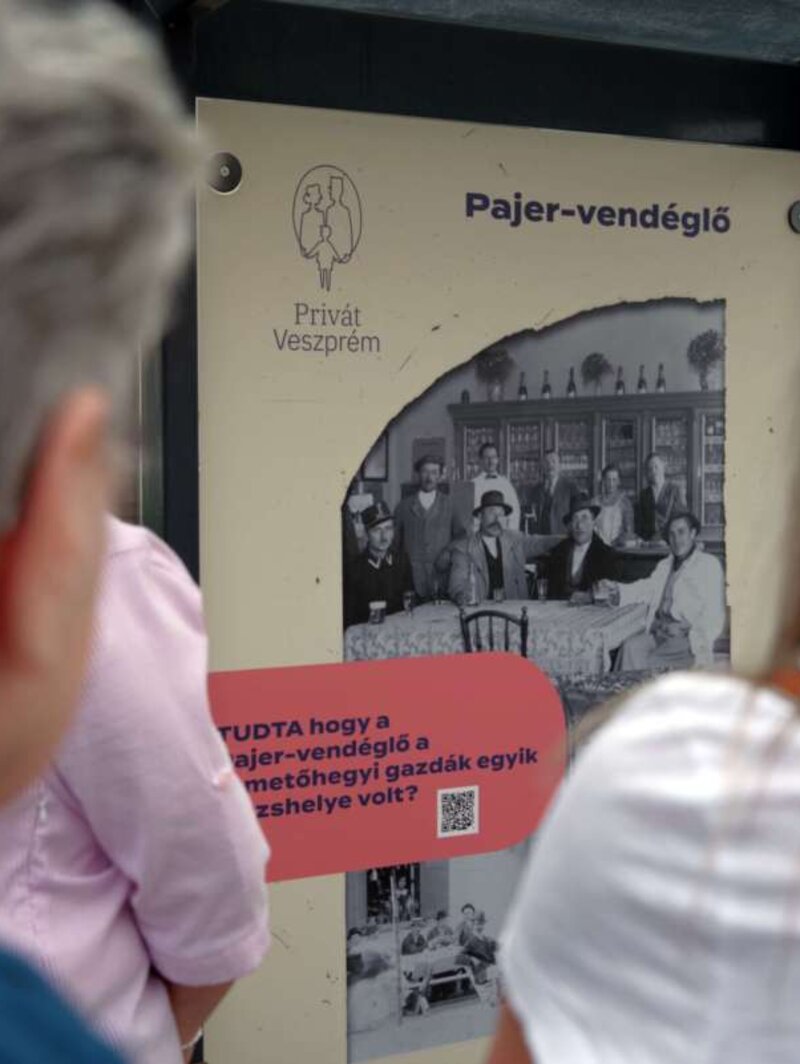

Storytelling Bus Stops: Pajer restaurant

The old house was located along the axis of the current viaduct (Valley Bridge), parallel to Pápai Street. Here, the Mélyút, the national road coming from Pápa, flowed into the city. Across from it, on the upper floor, was a poorhouse and a spice shop in the square, which was then known as Rohonczy Square and is now called Ságvári Square. The L-shaped building had its longer wing parallel to Pápai Street, while the shorter wing extended towards Betekincs Valley, separated from the neighbouring house's fence by an alley called "kisköz." The L-shaped structure enclosed a large courtyard and garden. In the middle of the courtyard stood a 'shed' supported by four columns, where guests' carriages and horses could wait. In the left corner, opposite the courtyard entrance, the peak of an ice cellar with a thatched roof protruded from the ground.

On the other side of the courtyard, a long stable building enclosed the space, and behind it lay the 'garden space', resembling a hanging garden, complete with a bowling alley and a small bar, bordered by walnut and horse chestnut trees, as well as lilac bushes. Here, from spring to autumn, there were lively beer parties and bowling events, especially on Sundays and holidays. On weekdays, service was only provided when city officials (i.e., municipal clerks) announced their arrival. One end of the rectangular garden overlooked the alley, featuring a covered arbour, while the other end extended toward the small cemetery near St Ladislaus' Church. The former cemetery was separated from the revellers by a high stone wall.

The main building, opening onto the street, featured a gated entrance suitable for vehicles, which was secured at night by a two-winged green gate, closed by the yard keeper. Everyone, including me, called the caretaker Uncle Imre. Guarding the entrance was a large black-and-white butcher's dog named Huszár. Beams supported the attic above the entrance, and numerous swallow nests were built on these beams.

To the left of the entrance was a long section of the building, in the centre of which a rolling door opened onto the large hall of the People's Circle, with an additional entrance from the entrance hall. This room was set with white tablecloths. In the centre stood a large billiard table covered in green felt, which could be flipped over. This space was open year-round for members of the Circle on Sundays and holidays. Here, winter dances were held, and the New Year’s pig dinner for 100 people was held, during which the billiard table was also set.

To the right of the gate was a section of the building with two street entrances: one led to the bar, a space that was open from dawn until 10 or 11 in the evening (not a standing bar, as patrons either sat and consumed leisurely or took their drinks to go), while the other led to the butcher's.

This so-called 'bar' was essentially a regular tavern. The spacious room was furnished with 5-6 round tables, each accommodating 6-8 people, along with straw-woven chairs and benches along the walls, covered with colorful tablecloths. The walls displayed the usual beer advertisements (depicting a girl offering frothy Dreher beer to hussars) and portraits of the martyrs of Arad. One corner of the tavern was enclosed by a two-metre-tall brown-painted wooden fence, which served as the actual 'bar' or emergency area. Shelves lined the wall, filled with numerous certified bottles of wine, along with wine glasses, beer mugs and cups. At that time, bottled or decanted wine was almost unknown. The beer tap was located on a counter that could be naturally cooled, along with two large earthenware jugs for wine, each holding 6.5 litres and decorated with handles. One jug contained 'common' wine, while the other held the 'better', more expensive variety. In the cellar, there were various types of wine stored in barrels, including those that were only rarely measured. I still remember that in the late 1920s—war or no war— Mariska wine was available, which, according to family tradition, my grandfather brought from Csopak when my godmother was born in 1883. It was a thick, almost black liquid—originally white wine—that was down to just a 30-litre barrel at that point, what remained from the original 8-hectolitre barrel. I recall they brought it up from the many steps of the cellar using a glass siphon, and they immediately refilled the barrel, with people tasting it from shot glasses.